|

"the culminating

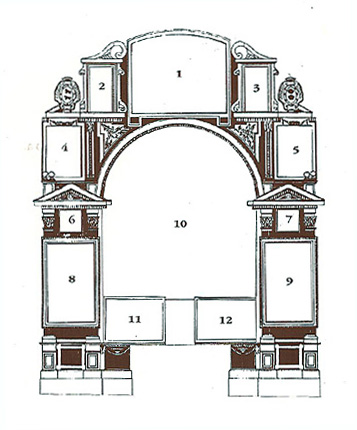

moment of Spanish baroque" Examining the Art in the Center of the Altarpiece |

||

|

|

10: The Rapture of Elijah

The center of the massive

structure is the Rapture of Elijah. One authoritative art critic on

Valdés Leal commented that the rapture of Elijah in the Córdoba altarpiece

dramatically contrasts with the poor movement portrayed in the Conception

which is in the Louvre and to which the painter is making reference. . . . The Saints of the Lower Section. There are four: St. Mary Magadelene de’Pazzi, St. Agnes, St. Apollonia, and St. Joanna de Tolouse. Valdés Leal employed the technique of showing three-quarters of the body, a Sevillian tradition, in these paintings. In general, the paintings portray respect for these saints “the serene beauty of these women is one of the greatest and impressive creations … A powerful natural light falls from the above left corner. The juxtposition of colors and simple shapes of the Carmelite habits, in contrast to the delicate tones and rich jewelry of the principal saints, is a one of a kind effect.” (Duncan, 76-77). The author brings out by the beauty and the feminine elegance of the women, admirable testimony to the fact that Valdés Leal is not just a painter of the macabre, as could be falsely concluded when looking at his paintings in the Hospital de la Caridad in Seville. 11: St. Mary Magdalene de'Pazzi and St. Agnes

St. Mary Magdalene de’Pazzi, “the mystic of love” (1566-1607), represents for the Carmelites that which St. Teresa of Avila is for the Discalced Carmelites; a principal focus of this age of spirituality was the baroque imagery of the exaltation of the Cross, focused in the Castellian saint, and that is what is displayed with the Italian Carmelite in the Córdoba altarpiece. The whimple of the Carmelite is typical for that time, if not without a certain touch of vanity in the dress, even though she is a nun. Nevertheless, the contrast between of garments of the two saints (Mary Magdalene and St. Agnes; Joanna of Toulouse and St. Apollonia) is evident, be it for the simplicity of the habit in one case as for the brocade, silk, and jewels in the other. Each carries the iconographic symbols for their lives that distinguished them: the two lay saints, St. Agnes and St. Apollonia, carry the palm of martyrdom showing that both gave their lives for the faith and love of Jesus, as well as symbols specific to each. St. Agnes is shown

with the typical white lamb of innocence and soothing lana, in contrast

with the violet color of the clothes and the gold brocade on the

sleeves, all highlighted in suave and contrasting colors resulting from

the light that shines on both saints from the upper left corner. A

delicate veil of red strips blows in the breeze, attached to her black

hair by a loop and a flower; meanwhile the viewer focuses on the lamb

that is being lovingly embraced; it is the Agnus Dei, the Lamb of

God, symbol of Jesus Redeemer who much earlier gave his life for all. A

halo, barely perceptible, surrounds the very beautiful face of Agnes. 12: St. Apollonia and Blessed Joan of Toulouse

St. Apollonia. The richness and color of her clothes overwhelms those of St. Agnes because the theme of her martyrdom is more difficult to portray with dignity and without wounding the sensibility of the spectator. Well known is the cruelty of the martyrdom suffered by the saint of Alexandria in the year 249 AD during the reign of Emperor Decius. To force her to renounce her Christian faith, all her teeth were knocked out, trying to disfigure her noble and beautiful face; Apollonia resisted martyrdom that ended when she jumped into a fire and then was decapitated. The painter presents her to us elegantly dressed in a fine green brocade with a belt, bedecked with adornments and jewels which befit a noble woman. Above the front is a diadem and a veil covers part of the her hair, adorned with other valuable pieces of jewelry. In contrast to the beauty and color of the robes and the jewels, she shows her bloodied teeth; the saint, nevertheless, with great naturalness, holds in one hand pliers. It seems that these dental pieces were later additions to this painting. Blessed Joan of Toulouse. Our saint lived as an anchorite next to the church of the Carmelites in Toulouse, in old Navarra, at the end of the 14th century and the beginnings of the 15th. She was, according to John Bale, her first biographer, one who “aspired to a life of penitence and spent nights in prayer… Daily she read the entire psalter.” Her reputation for holiness was such that, at her untimely death in 1452, the Archbishop of Toulouse himself, Rosier, allowed her cult and veneration; in a very beautiful fresco of 1472 in the Italian Carmelite house of San Felice del Benaco she is shown with a book in her hands in meditation and a crucifix, substitute sign for the lily which she holds in other paintings, as is the case in Córdoba. It is interesting that in the Córdoba altarpiece we are presenting here, the holiness of the female Carmelite is portrayed through its two most representative saints: Joan was the first female Carmelite beatified (1452) and Mary Magdalen was the last to arrive in the Carmelite pantheon, in 1626. The serene silence of these saints could well be attributed to the influence of Zurbarán according to Duncan. Palomino comments that these paintings are so perfect that they seem to have emerged from the hand of Velásquez.

|

|