|

no. 1 january - march 2007

Towards a Theology of Leisure Be Still and Know that I am God T he complex inter-connected nature of modern lives inevitably leads to the complexity of what individuals gain from and define as leisure. Only reflection by oneself can truly answer the question of what is the nature of leisure. There is an important role in facilitating healthy reflection. There is a need to free individuals to value leisure for leisure’s sake, to indulge in an experience which aids them to flourish as physical, spiritual and intellectual beings and moves them away from the values of status and productivity.Leisure at times will continue to be important as a way of re-energising and re-cuperating from work or seeking activities which have compensation qualities in relation to work or social roles, allowing an expression of different aspects of self and an exploration of other talents. Leisure can also provide the self-esteem, sense of belonging and autonomy that are absent elsewhere. Leisure should lead to the pursuit of humanitarian values which prevent an unhealthy attachment to work and work practices, that is, a more consistent and holistic approach to self and others – a development in the learning process of loving self and others. For the Order, the cost of not promoting and supporting leisure awareness and value will be higher than ignoring it. The promoting of life style balance and hence the recognition of the innate value of leisure is essential to a healthy respect for self and others, and for physical, mental and spiritual health. It is not only essential for effective, productive members but more importantly it is essential if we are truly to "love our neighbour as ourselves". Idleness does not equal leisure. It is about the need for balance and about promoting human flourishing as individuals and as community. People do gain meaning in their life through work, both paid and voluntary. A healthy lifestyle does not discourage this. It is the misuse of this and excessive work-centeredness which is to be avoided. Achieving a balance helps us move from a utilitarian, pressured view of work and the worker to one which is about work being a means of co-operating in God’s creativity and sharing in the delight of all that God makes. This balance helps us to see all aspects of life as delighting in God’s creation. Leisure is an essential part of that process and of the process of re-creation in Christ. The effective coming together of creative energy and relaxation in leisure ultimately leads to a contemplative, prayerful pursuit which forms an important part of our response to God - a response which allows us: to use what time is (or is made) available for leisure positively and freely with the discernment of what is good and profitable, a discernment which is part of the Spirit’s gift; and to recognize that prayer is not conditioned by "clock time" but is a total relationship with God that enables us to move easily from the day to day demands of life into a loving familiarity with God. Leisure is ultimately an essential part of a complete and healthy prayer life and response to God. Knowledge of God is in passivity not in effort, because effort presupposes a predetermined objective and one can have no preconceived ideas about God. When one is still (the object of true leisure) one doesn’t believe in God, one knows God. This is a very real response to the call to "Be still and know that I am God" or indeed to "Have leisure and know that I am God". Leisure in Today’s World While society at large struggles to confront and seriously address the emerging social problem of work-life balance, anyone turning to the Church and theology will face equal difficulty in finding guidance and support. There are four major approaches to leisure which highlight a number of key issues that need to be addressed. These approaches involve exploring: leisure as a concept of time, leisure as an activity, leisure as an attitude or state of mind and also the quality aspects to leisure. Time When we explore the approach to leisure which is time based, a recurrent theme is to start from the point where leisure is presented as time left over from work. I have worked hard this week. Therefore I earned time off. Such reasoning sets leisure and work in opposition. This concept of leisure prevents the freedom of discovery and expression that can be facilitated by an innate value to leisure. Leisure is benchmarked relative to other external expectations and roles. When this benchmark is specifically work, it often leads to a perception of the need to earn leisure. The leisure-work opposition which arises from the defining of leisure in relation to time can lead to very simplistic and constrained views and experiences of leisure. Some ministry arrangements open the individual to endure a 24 hour, 7 day a week ministry to fellow community members as well as to those who frequent our churches, sanctuaries, retreat centers, schools, etc. This can lead to a “feeling of never being off duty.” Quantifying and identifying specific blocks of leisure time can actually be quite difficult. This does not, however, entirely negate the time based approach when addressing life balance issues. The ability and/or willingness of an individual to identify any specific time slot which they would regard as their leisure time is often highly indicative of their lifestyle balance and their attitude towards it. An inability to indicate specific leisure time and space may mean the individual feels they cannot justify or have not earned the right to leisure. Activities We are most often presented with the identification of specific activities as leisure. This has led to the collation of numerous lists and directories of what are regarded as leisure activities. In turn, this has led to organisations facilitating involvement in such activities in a bid to encourage healthier lifestyle balances. Again, this is problematic as participation in such activities can, hence, lead to an automatic assumption that the individual is therefore at leisure. This “leisure activity” can, however, become another form of work. For some individuals, participating in some community social activities may be leisure. For others, this may simply be a way of fulfilling what they perceive to be the expectations of the community. Such activities will therefore be based around fulfilling role expectations and obligations and may not be experienced as leisure at all. Attitude To be truly at leisure involves much more than an allocation of time or a choice of activity. Leisure is much richer and much more personal then either of these will allow. Much of this richness of the leisure experience lies with the individual themselves and their perception of what constitutes a leisure experience. Leisure is in essence highly individualist and highly subjective. Different individuals will give value to different time, space and activities as leisure. It will also change as the individual changes. Often it is difficult for an older person to remember what was leisurely about some activity of their youth. An attitude-based approach to leisure also means that it may well take place in time which other approaches would regard as work. Painting a room in the monastery can be a dreaded chore for one person but a valued time of creative leisure for another. When leisure is defined using this approach, it is intrinsic to the individual and relies much more upon their attitude and perceptions. Qualities When exploring leisure time, leisure activities, and attitudes towards leisure there are constant references made to specific qualities associated with the leisure experience. The quality most often directly or indirectly claimed for leisure is that of leisure as re-creative. In part, this arises from the notion of leisure being used as restorative or as a means of renewal from and in preparation for the working day. This supports the perception of leisure being earned as a reward for work and has led to leisure-work opposition becoming an essential defining quality and leisure being valued from a utilitarian perspective. Leisure activities can provide real opportunities for a sense of autonomy, a sense of achievement, a sense of belonging and outlets for creativity and self-expression. To limit these qualities to being an antidote to the work experience or mere time filler is to define the individual from a starting point of productivity. To experience leisure qualities as intrinsic to the leisure experience requires a very different starting point which values leisure for leisure’s sake and regards the individual more holistically. Leisure for leisure’s sake can incorporate a large element of personal pleasure. The work ethic, however, limits the freedom individuals have felt in pursuing leisure for personal pleasure. Where work and productivity are highly prized and have strong societal approval and centrality, many find it very difficult to justify personal pleasure and even relaxation as motives for leisure. It seems that there is a hierarchy of acceptability which sees recuperation from or for work closely followed by more socially accepted motives which involve commitment to family, community or society at large as clearly superior to personal development and pleasure. It is not considered adult to be non-serious, non-productive, unpredictable, entertaining, fun, and creative. Yet an experience of community and the development of relationship skills which contribute to human/community flourishing can indeed be important by-products of the leisure experience which is sought for its own sake. This is especially the case where the leisure experience allows all masks to be dropped and a real connection to be made with others. Leisure time is also often linked to the quality of freedom, that is, time free from other obligations. Freedom—as in the phrase “free time”-- is seen as an important defining quality of leisure by most scholars. Freedom in a leisure context is usually viewed as involving freedom of choice, the pursuit of something from personal choice rather than because of external pressures or expectations. It is about an absence of imposition or obligation. Total abandonment of self and, therefore, total receptivity, opens the individual to a unique experience which allows growth, particularly spiritual growth, as opposed to simply seeking and earning a period of restorative activity. Such an experience of leisure, however, requires the development of key attitudes and skills in leisure which themselves are rarely addressed or explored. Our Order and Leisure There is little to be found in Church or the Order’s documents specifically on leisure. Worship and prayer could, however, be seen as the ultimate leisure experience given the skills and spiritual development which allow us to completely abandon ourselves to God, especially where prayer and worship are not confined to a prescribed ritualistic pursuit and are freely chosen. In Church based organisations we often find, however, that, with the best of motives, because the work can often more readily be seen as vocational or “forwarding the work of the gospel,” there is a tendency to encourage each other to “walk the extra mile,” and to achieve more than resources would normally allow. It is easy to become task focused, as well as focused on being seen to fulfil those extra requirements, rather than taking the time to be, and to reflect, on the way forward. It is easy to become focused on the individual as worker in such circumstances. Even prayer before the start of a meeting, with the best of intentions in contextualising the meeting, can become focused on simply equipping us to be effective at the task. A healthy approach to leisure means not just allowing effective recuperation from the working day but also respecting the need for life space outside of work - time for genuine leisure, time to be. This approach can no doubt at times seem counter to our commitments if we all rightly regard our work as not simply the way we earn a living but as part of the way we witness, an integral part of the way we live the gospel and are called to love. Nevertheless, there is clearly a need to confront religious values which compel any individual to work as hard as they possibly can. It does not promote the well-being of individuals, relationships or communities. Such a work-centered culture not only leads to ill health, poor performance, lack of motivation and the breakdown of healthy work and personal relationships, it denies our calling to “love our neighbor as ourselves”. The Way Forward When surrounded by a society that gives value and priority to productivity and utility the Carmelite community needs to challenge the lack of focus on the inner life and spiritual development. Our Order needs to create a community where individuals feel valued for who they are, not what they do. We need to strive to fill the void that leaves individuals inwardly starved and pressurized to be more and more productive and to prove themselves more and more through their “external” achievements. We need to promote a culture which allows individuals to value themselves and others enough to feel justified in seeking a more balanced lifestyle - a lifestyle which avoids over work as a way of feeling valued and earning respect or a need to invent pressures to prove their value. We need to challenge the sense of guilt that some feel in pursuing leisure in a work driven world, and free individuals to enjoy much needed leisure. We must strive to find a way to promote the inner calm and silence of leisure - a silence that is not necessarily about stillness but about a place or activity where we can relax and listen - listen to ourselves and to others. This should not be about “uneasy bursts of activity and unrewarding leisure, with which we seek compensation” but about opening us up to new possibilities and insight. Recognizing the importance of leisure, however, should not lead us to be so prescriptive and zealous with others that it becomes another area in which they need to be seen to be fulfilling expectations. We must not inadvertently force others into activities we may perceive as leisure. We need to respect and support individual choices which promote flourishing. In fact, we need to go much further than avoiding being prescriptive. The Church needs to encourage and build the confidence of individuals in exercising freedom and being fulfilled in doing so. Most of us are already aware that to flourish we need to address the leisure issue. We instinctively know that we need leisure. Many of us, however, need to be given permission to pursue the fulfilment of that need as a legitimate human need. Here the Order can play an important role in freeing individuals to pursue the lifestyle changes they need in order to move forward and flourish. Adapted from Hoose, J., ‘Embracing Leisure’ in Cullen, P., Hoose, B., & Mannion, G., Catholic Social Teaching, (Continuum, London, 2007). More excerpts from this article are posted on the CITOC website: carmelites.info/citoc. Jayne Hoose formerly a Senior Lecturer in the UK studied Moral Theology at King’s College, London and currently works as a Freelance writer and lecturer. She has published a range of articles, book chapters and books in the two disciplines of leisure and moral theology including the two internationally recognised books, Conscience in World Religions and An Introduction to Leisure Studies. [Jayne@bandjhoose.wanadoo.co.uk]

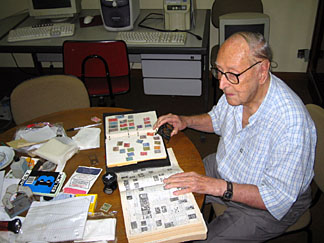

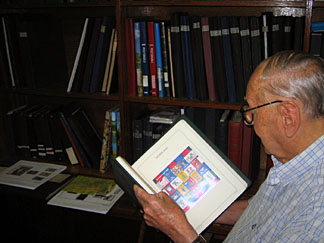

Few hobbies will endure as long as the stamp collecting of Carmelite priest Bento Caspes of the Flumen Januaris Province in Brazil. Born in Zuid-Holland, the Netherlands in 1914, he began collecting stamps at the age of 10. He started his hobby with just Dutch stamps. His mother was very interested in collecting small things. It was an interest she passed on to her son. In 1933 Bento was sent to Brazil and he brought his entire collection with him. He continued his hobby in Brazil, expanding it to include stamps from various countries. So after 83 years, how many stamps are in the collection? "I have no idea," Fr. Bento says, barely pausing from looking through a book containing colorful stamps from the Vatican. His Vatican collection contains every stamp issued since Pius XI. He has stamps from European nations and "almost all" of the countries in Latin America. The most complete collections are that of the Vatican, the Netherlands, Brazil, and Indonesia. He also worked to build up special collections with religious themes. "I have many from North America but I stopped buying them in 1993. They became just too expensive." It has been a major time commitment. He arrives at the stamp room at four in the afternoon and works for 90 minutes to two hours every day. His office is a large room wall to wall with shelves full of stamp books. The tables have more stamp books and stamps awaiting Bento’s careful placement in their proper book.

Which is his favorite collection? The stamps with a religious theme he says and then proceeds to pull more books off various shelves to show them off. Was there ever another leisure activity that interested Fr. Bento? "I tried painting. I did four or five pictures and then gave it up." If someone in the United States wants to exchange stamps, Fr. Bento is ready and willing after a 14 year pause. "Now I want to build up that collection!" Bento Caspes, O. Carm., with a small portion of his stamp collection. (CITOC photo)

Teodoro Brovelli entered Carmel in March 1997 and made his Solemn Profession on October 7, 2006 at the Carmine in Florence, Italy. From the time he was 14 years old, he studied furniture restoration "as working with wood has always been my passion," he said. "I worked eight years as a framer." Now Teodoro is in the formation program at San Martino ai Monti in Rome, in the first year of theology. "In my free time, I try to work as carpenter and factotum in the house." "In the year of preparation for Solemn Vows, I lived in the Carmelite community of Nocera Umbra where I was able to build the community chapel. Everything is wood: floor, windows, benches and small racks for the various prayer books. I also built a bookcase three meters tall and four meters wide, everything in wood." "I could do this thanks to the equipment that the community bought believing it useful in that it is important to work in the apostolate and also do some manual labor. In fact the Rule says "You must give yourselves to work of some kind, so that the devil may always find you busy … this is the way of holiness and goodness: see that you follow it" (Rule 20). "During a retreat last year in a monastic community, I restored a very antique bread storage case, that is now being used as an altar, in a chapel in their garden." "In the Rule, it says ‘the brothers are to stay in their own cell or nearby, pondering the Lord’s law day and night and keeping watch at prayers unless attending to some other duty.’ (Rule 10). I assure you that provision of the Rule is not easy in a city like Rome because you leave your cell and you find confusion, traffic, and smog. So that is why I sought to create a space, a laboratory, where, when I manage to carve out a minute between studies and community commitments, I can work on icons with various images of Our Lady, Christ Pantocrater, and angels. It is a simple work that takes me to a very intimate place with my God. Only when I finish do I realize that a lot of time has gone by since I started working. I think that the talents we can have (painter, restorer, musician, and many others) can be held in esteem in religious life. For me, for example, working with wood "relaxes my body and my spirit" and is a means to continuous prayer." Teodoro Brovelli, O. Carm., in his woodshop at San Martino ai Monti, a Carmelite parish and formation house in Rome, Italy.

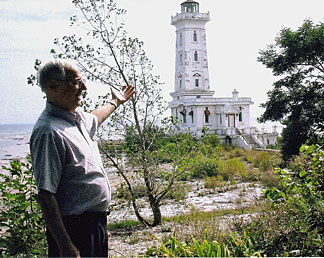

"As long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by lighthouses. I grew up not too far from the ocean. Every summer my family rented a cottage for three weeks at the shore. Nearby there was a lighthouse still in service. Every summer I would visit this particular lighthouse and soon I got to know the lighthouse keeper. Often he would give me books and articles to read about the history of lighthouses all over the world. He also gave me maps of lighthouses which I found intriguing. Soon, lighthouses became my hobby!" says Roger Bonneau, a Carmelite at the Carmelite Spiritual Centre in Niagara Falls, Ontario in Canada. "From my reading about the history of lighthouses, I learned that perhaps the most famous lighthouse in the world was the lighthouse of Alexandria, built on the Island of Pharos in ancient Egypt. The name of the island is still used as a noun for ‘lighthouse’ in some languages, for example, French (phare) and Italian and Spanish (faro). Because of modern navigational aids, the number of active lighthouses has declined to less that 1500 worldwide." "As a Carmelite I have had assignments in Texas, California, Illinois and Canada. This has given me the opportunity to visit some of the 700 lighthouses that encircle the coast line of the United States and the Great Lakes." "Lighthouses are powerful symbols for me. In a world so often filled with darkness and death, lighthouses have been sources of light and aids to life. Lighthouse keepers have to be dedicated individuals, able to spend long periods of time alone. Also, they have to be people of faith because very seldom do they get to meet those they guide through dangerous waters. Our Carmelite vocation calls us to be a light shinning in the darkness, as well as people of faith who are willing to spend time alone with God." Roger Bonneau, O. Carm. and one of his lighthouses at Albino Point, just outside Fort Erie, Ontario in Canada. |

|

RETURN TO THE INDEX FOR 2007 | RETURN TO THE INDEX FOR THIS ISSUE INDEX OF CARMELITE

WEBSITES |

If, after 83 years, he has forgotten where some of the stamps are, he

does not let visitors know. He also remembers how he came into possession

of most of the individual stamps. The day we spent with him, he was

working on Venezuelan stamps from 1938-1947. He easily picked books off

the shelf to show us particular stamps he thought we would enjoy. He

opened up the page to a stamp from 1880, allowing his visitors to

carefully examine it under a magnifying glass. He received that particular

stamp from a fellow who gave up the hobby and gave his entire collection

to Bento. He receives stamps from all sorts of people. He will still buy

some from the Netherlands and Brazil.

If, after 83 years, he has forgotten where some of the stamps are, he

does not let visitors know. He also remembers how he came into possession

of most of the individual stamps. The day we spent with him, he was

working on Venezuelan stamps from 1938-1947. He easily picked books off

the shelf to show us particular stamps he thought we would enjoy. He

opened up the page to a stamp from 1880, allowing his visitors to

carefully examine it under a magnifying glass. He received that particular

stamp from a fellow who gave up the hobby and gave his entire collection

to Bento. He receives stamps from all sorts of people. He will still buy

some from the Netherlands and Brazil.